In their hunger for power, humans have always searched for the perfect weaponry. Empires carved out in history were often the result of strategic planning, political ingenuity, and the most sophisticated warfare of their time. The careful selection of weapons at times proved to be the crucial difference between winning a battle or being slaughtered on the field. The earth has been bled upon during times of war from one century to another, the only difference being the style and choice of the weapon wielded.. very weapon is made with a specific purpose in mind. Weapons are constantly evolving to meet the needs of the warriors who wield them. Sometimes though, these needs produce weapons that, while no less efficient at executing their purpose, are ultimately quite unique.

10- Kakute

Photo credit: Hyakuraiju

kakute were spiked rings used in ancient Japan. Though a similar weapon called the “shobo” was made of wood, kakute were usually iron and had from one to three spikes. A user would generally wear either one or two rings—one for his middle or index finger and another on his thumb. The spikes were usually turned inward and applied to pressure points by gripping limbs or even the neck, which wound stun an opponent and cause a nasty puncture wound. Turned outward, kakute became spiked knuckledusters, though since the purpose of kakute was generally to subdue enemies rather than harm them, this style was not the standard.

Ninjas also used kakute. They were favored by female ninjas, called kunoichi, for whom it was natural to wear rings. Worn inward and tipped with poison, they could use their kakute for quick, fatal attacks. For the female ninja, they proved to be one of her deadliest and most efficient weapons.

9- Haladie

Photo credit: VikingSword.com

Many interesting weapons came out of ancient India, but among the most dangerous was the haladie, a weapon of India’s ancient warrior class, the Rajput. The samurai of India, Rajput lived a lifestyle dedicated to fighting and honor, using weapons like the doubled-bladed haladie knife to cut down their enemies.

Haladie had two double-edged blades connected to the ends of a single handle. It was believed to be a thrusting weapon, although the slightly curved blade could just as easily be used for slashes and parries. Some types of haladie had a metal band similar to knuckledusters covering one side of the handle, where yet another spike or blade could be attached. Almost like something out of a fantasy novel, those types of haladie were perhaps the world’s first triple-bladed daggers. An army of ancient Indian warriors would have proven quite intimidating, equipped with both the haladie and their famed double-edged scimitar, the khanda.

8- Sodegarami

The sodegarami, meaning “sleeve entangler,” was a weapon of the Edo-era Japanese police. Often used by a pair of officers, the sodegarami was a spiked pole they would slide into an opponent’s kimono. A quick twist would entangle the fabric and allow officers to bring the offender down without causing (too much) injury. Often, one officer would attack from the front and another from behind, working together to pin the criminal to the ground by their neck. Having two sodegarami tangled up in your kimono made it almost impossible to escape.

It was an important tool for arresting samurai, who by law could only be killed by other samurai. Once an offending samurai drew his katana, an officer would slip his sleeve grabber up the samurai’s kimono to entangle him. He would then bring the samurai down non-lethally to avoid unnecessary bloodshed.

7- Zweihaender

Perhaps the largest type of sword in history, the Zweihaender was famed for its use by Swiss and German infantrymen to fight off pikes. Zweihaenders were two-handed swords that stretched upward of 178 centimeters (70 in) and weighed anywhere from 1.4–6.4 kilograms (3–14 lbs), though the heavier examples tended to be purely ceremonial. Primarily used against pikes and halberds at longer ranges, some also had an unsharpened part of the blade—called a ricasso—just above the primary guard. The ricasso could be gripped in close quarters combat. These kinds of Zweihaenders usually had a smaller, secondary guard that protruded from the main blade.

Soldiers who used these immense swords received double pay. The Landsknechts, a feared mercenary band so well respected they even received special exemption from sumptuary laws to maintain their flamboyant dress, helped make them famous. Despite their popularity, however, Zweihaenders eventually gave way to the easier-to-handle pike and became mostly ceremonial. Though they had once been a frontline weapon, advancements in technology eventually regulated them for use by shock troops and mercenaries. In some cases, Zweihaenders were even officially prohibited from battle.

6- Madu

Photo credit: Karthik Nadar

Fakirs—ancient Muslim and Hindu ascetics and mendicants—were not permitted to carry weapons, so they had to improvise to protect themselves. They created the madu, which was apparently not officially considered a weapon. The weapon (let’s face it, that’s what it was) was originally made from two Indian antelope horns connected perpendicularly by a crossbar. With the horn tips at opposite ends, the madu, or “Fakir’s horns,” was excellent for stabbing, though the fakirs considered it to be primarily for defense.

The style of fighting with the madu is still practiced today. Called maan kombu, it is a part of the larger art of silambam: an ancient, weapons-based Indian martial art. Maan kombu (“deer horns”) is named after the weapon’s material, as fakirs and silambam artists eventually began using other kinds of animal horns. The art form is dying, however, as current laws prohibit the use of deer or antelope horns. There are several variations of the weapon, including one with added steel tips and a shield, making the madu an even more efficient weapon.

5- Fire Lance

Developed in ancient China, the fire lance was a spear-like weapon that fired a projectile with gunpowder. The earliest form was a simple bamboo tube packed with sand that was strapped to a spear. Such a weapon would have been able to blind an enemy and give the wielder the advantage in close quarters combat. As technology evolved, though, fire lances started to incorporate shrapnel and poison darts. But explosions strong enough to launch these projectiles required stronger housings, and fire lances began to be made first of a strong type of paper and then finally metal.

Accounts also describe a weapon called a “fire-tube” being used as a flamethrower to shower enemies with flames that were 3.5 meters (12 ft) tall. Further developments led to poisonous chemicals being mixed with the explosive mixture, which would cause the unfortunate victim’s burns to go septic. Less of an explosion and more of a steady stream of flame, weapons like these would belch “poisonous fire” for an estimated five minutes before burning out.

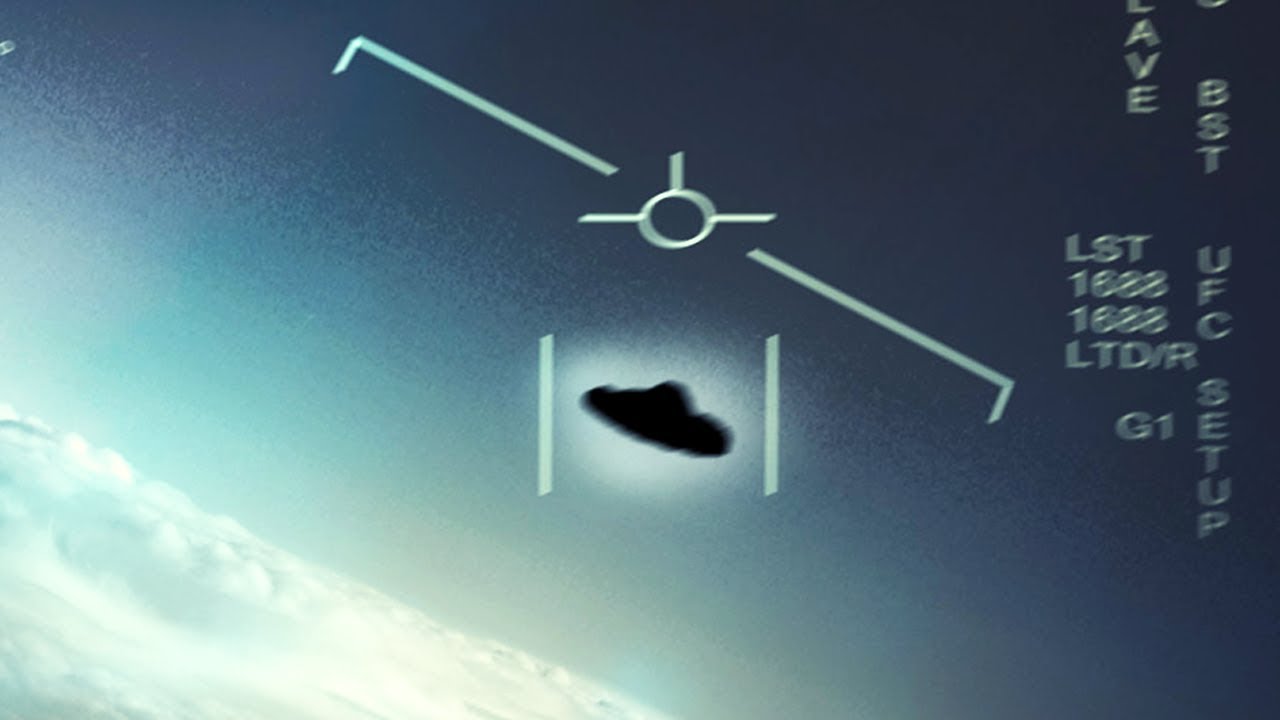

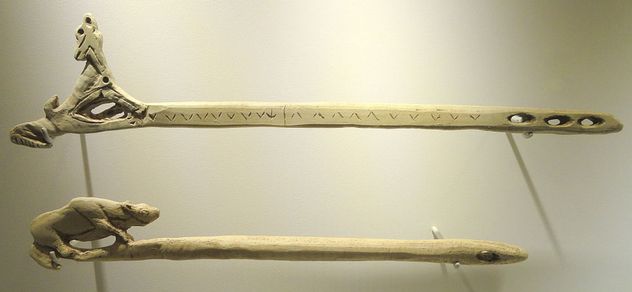

4- Atlatl

A Stone Age dart weapon, the atlatl was the precursor to the bow and arrow. While spears could only be thrown at limited speeds and distances, atlatl could launch darts at over 160 kilometers per hour (100 mph). It was a deceptively simple weapon, nothing more than a handheld stick with a protrusion or notch at one end where a dart could be set. Yet despite their simplicity, atlatl were so effective that it’s even been theorized that they contributed to the extinction of the woolly mammoth they were used to hunt.

The weapon’s speed came from its flexibility. Both the atlatl and the dart were made of flexible wood. The two parts bent simultaneously when the atlatl was fired, which allowed the energy stored in each to launch the dart at very high velocities. Archaeological evidence tells us that the use of the atlatl was also widespread, with examples found in every inhabited continent except Africa. Though they were eventually replaced with the easier-to-use bow and arrow, the atlatl stood the test of time, being used by the Aztecs even as late as the 1500s.

3- Khopesh

Photo credit: Aoineko

Although sometimes called a sickle-sword, the ancient Egyptian khopesh was more of a cross between a sword and a battle ax. During earlier Egyptian times, the mace represented ruling power, but the khopesh‘s deadliness on the battlefield eventually made it the preferred status symbol of Egypt’s elite. Even Ramses II was depicted wielding one.

A Bronze Age weapon, the khopesh was usually cast out of a single piece of bronze and could be quite heavy. It’s believed to have been an Egyptian adaptation of a large, two-handed weapon similar to a war ax, imported from Canaan and Mesopotamia. The blade had a pronounced curve, like a sickle, though only the outside edge was sharpened. Much like the battle ax, the khopesh could be used as a hacking weapon, though its shape also made it efficient at slashing. The inner part of the curve was equally functional and could trap an arm or yank away an opponent’s shield. Some had small snares for that very purpose.

2- Shotel

Photo credit: VikingSword.com

Unlike the khopesh, the shotel was a true sickle-sword once used in ancient Ethiopia. Its shape made it extremely difficult to block with another sword or even a shield—shotel would just curve around it to puncture the defender. Despite that and its vicious appearance, it was almost universally considered useless.

The hilt was too small for a large, scythe-shaped blade, which made it an unwieldy weapon to hold or aim properly. Fighting with a shotel proved quite difficult. Because of the shape of the blade, even drawing it from its scabbard was somewhat awkward. Scabbards stretched a foot longer than the swords themselves and were worn pointing behind the owner, which meant drawing it with the blade facing the correct way required a large bend of the wrist. European accounts of the weapon were extremely negative, and even the Ethiopians themselves considered shotels little more than ornamental. They had a saying about the shotels that essentially deemed the weapons useful for nothing more than impressing women. We suppose some weapons were just meant for a different kind of battle.

1- Urumi

Urumi were flexible sword whips. The blade itself was made of extremely bendable metal that, when not in use, could be wrapped around the waist like a belt. Blade lengths differed, but urumi could reach lengths of 3–5 meters (12–16 ft).

Urumi were whipped in circles, creating a defensive zone difficult for an opponent to penetrate. With both sides of the blade sharpened, they were extremely dangerous even for the wielder and required years of training. Even simple things like stopping the weapon and changing directions were considered special skills difficult to master. Due to the unique fighting style, urumi could not be used in battle formations and were better suited for man-to-man combat and assassinations. Yet despite the stringent requirements for wielding one properly, they were an unstoppable force once mastered. Parrying proved almost useless against an urumi, because even if an opponent tried to stop it with a shield, the urumi would just bend around it to strike.